Coast Redwood and Giant Sequoia Mega-Genomes Sequenced

Sequencing Brings Modern Tools to Redwood Conservation Efforts

Scientists have successfully sequenced the coast redwood and giant sequoia genomes, completing the first major milestone of a five-year project to develop the tools necessary to study these forests’ genomic diversity. The research partners, composed of the University of California, Davis, Johns Hopkins University and the Save the Redwoods League, are making the data publicly available today.

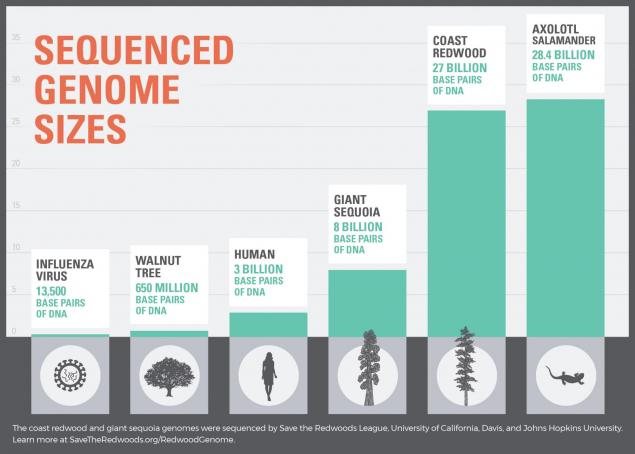

The coast redwood genome is now the second-largest ever sequenced at nearly nine times the size of the human genome. The genome of the giant sequoia is roughly three times that of the human genome.

‘23 and Tree?’

Much like sequencing the human genome opened the door to finding cures for things like sickle cell anemia, sequencing the redwood and sequoia genome could help conserve and restore those species.

“Our patient is the redwood forest,” said David Neale, professor in the Department of Plant Sciences at UC Davis. “It’s not healthy. We seek to make it healthy again, and we need that same foundational resource as a human physician or medical professional needs for their patients.”

Over the past 150 years, 95 percent of the ancient coast redwood range and about one-third of the giant sequoia range have been logged. With this unprecedented loss of old trees and the addition of redwood clones often planted in their place, conservationists have grown concerned that the forests’ genomic diversity has fundamentally changed. If diversity has declined, it could leave the redwoods vulnerable to drought, fire and other stressors related to climate change.

By sequencing these trees’ genomes, the scientists are providing a tool that resource managers can use to help discern a redwood forest’s genetic potential for adapting to its current or future environment.

“We’re trying to build a 23andMe for trees, where a manager sends in their samples and gets a risk evaluation of their forest populations, if not individual trees,” Neale said. “Completing the sequences of the coast redwood and giant sequoia genomes is the first step.”

Sequencing conifer ‘mega-genomes’

These conifers have giant genomes, and full sequencing of them has only been possible in the last decade.

The coast redwood has six sets of chromosomes (hexaploid) and 27 billion base pairs of DNA. The giant sequoia has two sets of chromosomes (diploid) and over 8 billion base pairs. For comparison, the largest genome sequenced to date belongs to the axolotl, a North American salamander whose genome was completed in 2018 and has more than 28 billion base pairs.

“We pushed the boundaries of genome-sequencing technology to take on the redwood and sequoia mega-genomes,” said Steven Salzberg, professor of biomedical engineering at Johns Hopkins University. “After using our specially developed algorithms to assemble these enormous and complex genome sequences, we have gained a new appreciation for how difficult it is to put together a hexaploid genome, especially one as large as the coast redwood’s.”

What’s next?

The redwood genome project was launched in late 2017, with a projected five-year timeline. By the end of the project, the genome sequences and screening tools developed will allow field crews to quickly assess adaptive genomic diversity in redwood forests to inform management plans that restore the health and resilience of these forests throughout their natural ranges.

With the genomes sequenced, the league will work to inventory diversity across the landscapes and identify “hot spots” of genomic diversity for enhanced protection and areas of low diversity for restoration.

“Every time we plant a seedling or thin a redwood stand to reduce fuel loads or accelerate growth, we potentially affect the genomic diversity of the forest,” said Emily Burns, director of science for Save the Redwoods League. “With the new genome tools we’re developing now, we will soon be able to see the hidden genomic diversity in the forest for the first time and design local conservation strategies that promote natural genomic diversity. This is a gift of resilience we can give our iconic redwood forests for the future.”

The coast redwood and giant sequoia sequence data are available to the scientific community at large through the UC Davis website.

During the next stage of the project, researchers will create a database capturing range-wide genomic variation within each species; develop tools that will allow resource managers to identify coast redwood and giant sequoia genetic variation while in the field; compile forest genetic inventories; and launch pilot restoration projects based on the accrued data.

“When we celebrated the league’s 100th anniversary last year, we reaffirmed our commitment to restore entire landscapes of young, recovering redwood forests,” said Sam Hodder, president and CEO of Save the Redwoods League. “Sequencing the coast redwood and giant sequoia genomes for the first time opens a new scientific frontier for our restoration projects. This work will reveal the forests’ genetic identity so that we can protect the diversity that’s left, and in some areas, restore what was lost.”

Major funding for the research came from Save the Redwoods League. A significant lead gift to the league to fund the initial sequencing of the genomes was provided by Ralph Eschenbach and Carol Joy Provan.

Media contact(s)

Kat Kerlin, UC Davis News and Media Relations, 530-752-7704, kekerlin@ucdavis.edu

Ashley Boarman, Landis Communications Inc., 415-359-2312, redwoods@landispr.com