How California became a food and wine lover's dream

If you’ve ever taken a drive through California’s picturesque vineyards and pastoral farms, you know it’s impossible to imagine the Golden State without them. But California wouldn’t have become a dream destination for foodies and oenophiles without research from the University of California.

Today, California rivals France, Italy and Spain as a global wine producer, contributing billions of dollars each year to the economy. California also produces a majority of the nation’s fruits, vegetables and nuts, and a large portion of its livestock and dairy, with yearly production valued at more than $50 billion.

That wasn’t always the case. In 1860, New York was America’s top dairy state, Ohio led the nation in winemaking and California trailed 27 states with its farm value of less than $50 million.

California’s rise in agriculture, including its reputation for producing world-class wine, has gone hand in hand with the work of researchers and scientists at the University of California.

In the late 1800s, UC soil scientists led the foundational research that showed farmers how to remove salts from the alkali soils in the Central Valley, transforming barren land into one of the the world’s most productive farming regions. UC researchers also helped establish California’s wine industry, then brought it back from the brink after prohibition nearly destroyed it.

Its partnership with farmers, vintners and ranchers is just as strong today, with cooperative extension offices in every county in the state.

A new industry takes root

UC launched its Department of Viticulture and Enology in 1880, after being directed by the state legislature to help California develop its nascent wine industry. UC agriculture professor Eugene Hilgard, director of the first State Agricultural Experiment Station, led the charge.

California can hardly fail to become one of the foremost grape-growing countries of the world, since it possesses all the natural advantages.

Eugene Hilgard, UC College of Agriculture, Supplement No. 1 to the Report of the Board of Regents, 1890

He was convinced that the California climate made it ideal for winemaking, and thought that with the right techniques, the state could move beyond the “faulty wines” being currently produced to create something truly worth drinking.

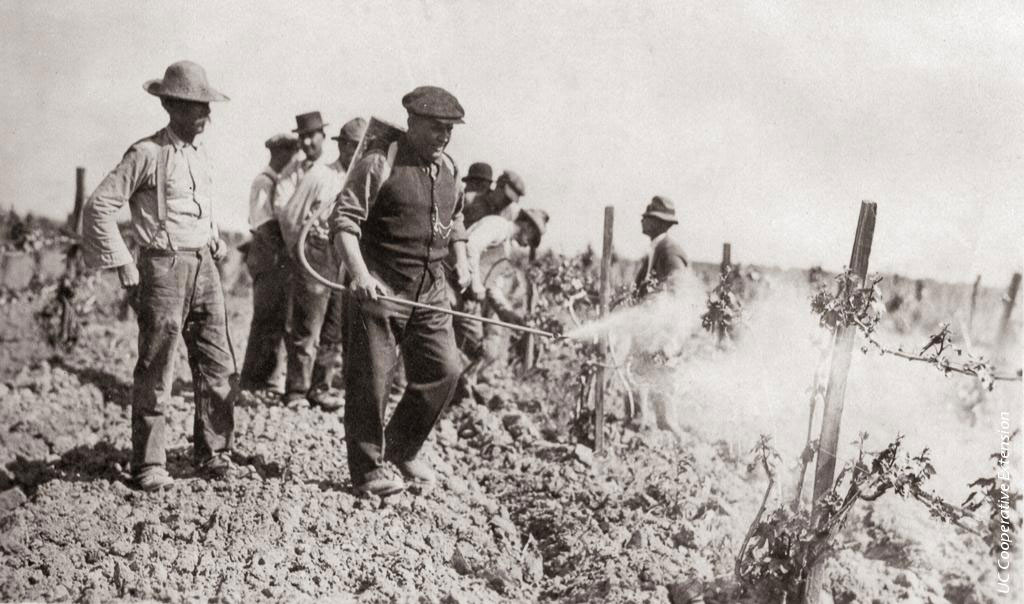

While the Mediterranean weather in California was perfect for growing grapes, on the ground there was confusion about varietals, crude and insufficient fermentation processes and an infestation of the root louse, phylloxera.

Hilgard began studying California’s soils and developing phylloxera-resistant plants at the university’s farm at Davis. By 1919, California’s young wine industry was beginning to flourish when Prohibition brought things to a screeching halt.

Hundreds of wineries went out of business. Farmers tore out their vineyards and planted fruit trees. UC’s enology program ended, too, but its work on grape growing and fruit production continued.

By the time Prohibition ended in 1933, UC was an established authority on grape growing in California, and it stepped in to help the wine industry recover.

UC Davis launched its Department of Viticulture and Enology in 1935, and hired plant physiologist Maynard Amerine. Over the coming decades, Amerine and his colleagues developed detailed information about which wine-making grapes would grow best in which climates. Their 1944 study on grape zones gave detailed information about where to plant grapes for different types of wine, such as chardonnay or cabernet.

That discovery recharged the wine business in California, and was the foundation of the appellation system that is still used to this day. Tailoring the varietals to California’s microclimates revolutionized grape growing in California, leading to better harvests, better fruit and ultimately, better wine.

My bible was [UC Davis professor] Maynard Amerine’s ‘The Technology of Winemaking.’ I learned to make wine only because I followed that book so religiously. I succeeded because of that.

Robert Mondavi

UC researchers haven't just helped produce wine — they'll also help you drink it. At least that was the goal of UC Davis professor of viticulture and enology Ann Noble, who in 1984 grew tired of hearing people describe wine with abstract and highly subjective terms like “harmonious.”

Her wine wheel (find a downloadable version of the wheel here) is designed to help consumers pin down the aromas they like with increasingly specific language. Do you like your wine “woody”? If so, is it “burned” or “resinous”? Does it have hints of “tobacco” or “cedar”? Noble's wheel spread like wildfire and has now been translated into eight languages for the connoisseur's delight.

From barren land to the world’s breadbasket

UC research has helped to grow more than just grapes. Through the Cooperative Extension and in-depth research by its campuses, UC has worked with California farmers in almost every aspect of food production, from developing new crop varieties to fighting pests to determining the most efficient ways to irrigate and conserve water.

UC’s partnership with farmers and growers stretches all the way back to Eugene Hilgard, the legendary 1880s soil scientist. He led much of the foundational research that showed farmers how to remove salts from the alkali soils in the Central Valley, turning what was once barren land into one of the world’s most productive farming regions.

In the early 1900s, the university deepened its agricultural research by establishing the University Farm (which would become UC Davis) and the Citrus Experiment Station (which would become UC Riverside).

Over the years, these two campuses have become internationally renowned for their agricultural expertise. UC Davis developed nearly half of the world’s strawberry cultivars, for example, while Riverside and the division of Agriculture and Natural Resources is responsible for producing 40 new citrus varieties.

UC also branched out into the counties under the leadership of B.H. Crocheron, who joined UC in 1913 and directed the UC Agricultural Extension Service from 1919-48. Buoyed by the Smith-Lever Act that created Cooperative Extension, Crocheron developed a network of farm advisors, who worked to get important research-based knowledge from campuses to the community. As Crocheron said, the farm advisor’s work “is on the farms and among the people."

UC research continues to evolve with the agricultural needs of the state. Today, UC researchers are focused on addressing the challenge of climate change by building sustainable local and regional food systems, a resilient water future and integrated pest management systems to ensure a prosperous future.